by Anna Firth

A critique of gender critical ideology through the lens of The Handmaid’s Tale—is dressing in red and defining womanhood by childbirth something we wanna be doing?

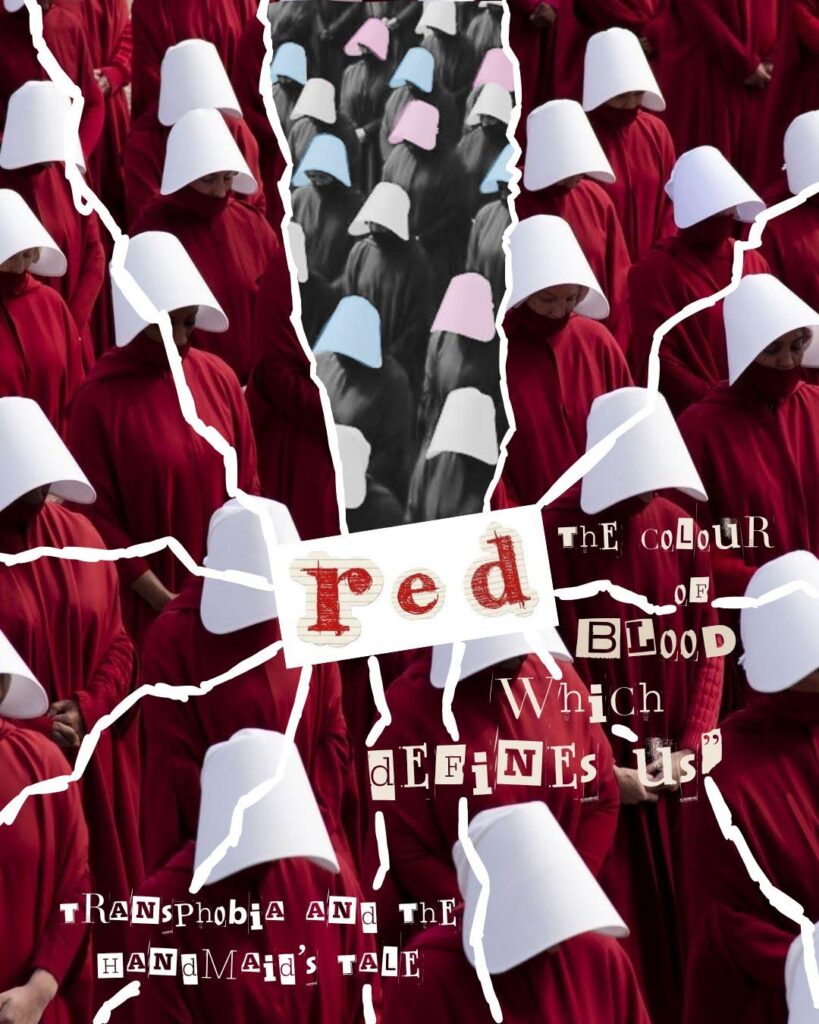

About a year ago, I saw a tweet about “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF) day of visibility”. In a reply discussing the event, a user wrote, “The best colour for us to wear will be red (…) the colour of the blood we shed monthly and in childbirth – two things that the male colonisers cannot do.” When I saw this tweet, it had 972 likes. That tweet stuck with me — not just for its message, but because its idea of blood as the defining marker of womanhood reminded me of similar imagery I’d recently encountered in a very different context.

That week I’d begun studying The Handmaid’s Tale as part of my A-level English Literature course. It’s a book often referenced in conversations about women’s rights— I’d guess it’s a book that many self-identified TERFs would point to. I know it’s a book my mother enjoys.

The protagonist of the novel is Offred, a woman in the dystopian society of Gilead, which is suffering from low fertility rates. Offred’s purpose as a “Handmaid” is to conceive a child on behalf of wealthier women. Her movements, language, and presentation are heavily controlled by the oppressive society she lives in. Offred is defined entirely by her body. She’s objectified for her fertility, she “avoid[s] looking down at my body … I don’t want to see it. I don’t want to see something that determines me so completely.” Offred hates the fact that she’s only seen for her body, reduced to biological functions. Her self-expression through clothing is limited to a uniform, a shapeless dress of pure red. As Offred describes it: “Red: the color of blood, which defines us.”

You can probably see where I’m going with this.

The Handmaid’s Tale is a novel that heavily criticises militaristic boundaries between gender, both literal and figurative. It points out how tying womanhood to menstruation or childbirth feels not only limiting but alienating. For me, this association reduces my identity to a biological process I didn’t choose and a function that many women, including myself, cannot or do not wish to fulfil. This perspective excludes trans women, intersex people, and infertile women, overlooking the true diversity of womanhood. Ideally, womanhood should be defined in a way that celebrates its full range and the unique meanings it holds for different individuals. I don’t want to be recognised for doing things that “male colonisers cannot do”; I want to be recognised for the things that I can do. I find it ironic that the imagery being used to “empower” women on twitter (delete your twitter account by the way, it gives you brainworms), was the same as what was used to characterise the dystopian society of Gilead with its repressive gender roles. It’s a strange inversion, to see the Gender Critical movement co-opting the motifs of Gilead to supposedly protect women- whereas in The Handmaid’s Tale it’s the symbols of female oppression itself.

A common TERF talking point is the dire need for “safe spaces for (cis) women”. Spend too long looking at TERF-made content and you begin to see women as this eternally harried group, a species that needs protecting from leering predatory men trying to infiltrate the community.

Yeah, we live under a patriarchy. It sucks. But I can’t help thinking there’s a better long-term solution than simply avoiding encounters with cis men at all costs. Instead of stifling the symptoms of a deeper problem – these individual acts of male violence against women- society could focus on the deeper systemic source behind this gendered violence. Instead of placing women into safe spaces, we could focus on educating predatory men.

I think when someone believes men are ‘inherently evil’, it leads to deepening prejudiced thinking as it assigns these predetermined roles onto people. It assumes that someone biologically male is ‘inherently bad’, that they could never change, and it’s almost inevitable for them to do bad things. It’s missing the point of ‘all men’ by literally talking about every individual man rather than the system that causes the behaviour.

We could address the “male loneliness epidemic” and the “manosphere” podcasters presenting the idea that a man’s role should be forcing women to submit to him. We could talk about pickup artists that treat women like biological puzzle boxes which can all be solved by the same solution. What these narratives have in common is exploiting the perceived intrinsic differences between men and women. By leaning into these divides and the supposed deep-rooted biological differences between sexes, and misogyny is further perpetuated.

To combat this, I believe transgender individuals can be hugely beneficial in bridging this divide between men and women. Being able to pass as a gender other than your assigned one at birth allows you to literally see the issue from both sides and allows for a unique perspective that cisgender folk cannot have. That perspective could be incredibly valuable for providing empathy and understanding across the gender spectrum— something I think is needed for ending misogyny that stems from ideas of biological essentialism and the inherent nature of women.

The TERF movement focuses on creating a harsher divide between cis men and cis women in the name of advancing women’s rights but it reduces people down to biological functions, enforcing overly militaristic borders on gender roles. The Handmaid’s Tale was written in the mid-1980s, and Atwood was inspired by both the past and contemporary political climate of America to envision the future for her dystopian speculative fiction novel. In response to second wave feminism in the US, there was a countermovement of the “New Christian Right”, composed of multiple large lobbying organisations such as the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition, that opposed abortion and focused on the preservation of “traditional family values” and by extension, the gender roles associated with them. Like the contemporary political figures that inspired the novel, TERFs are enforcing gender roles under a new guise.

Within The Handmaid’s Tale, female oppression can also be perpetuated by women themselves — a fact I believe should be kept in mind. The feminist movement itself is not free of criticisms: the moral panic of the “Lavender Menace” and the exclusion of women of colour, show how feminism has at times been hostile to women with less privilege. Each wave of feminism, while expanding the conversation about gender equality, has also drawn boundaries around who is “woman enough” to belong. Today, that boundary is most often drawn against trans women. It can be uncomfortable to confront that feminism has sometimes perpetuated inequality, but let’s stop history from repeating itself. A movement that defines itself by exclusion will only redefine the boundaries we’re confined by. As Margaret Atwood said: “Those stuck on nature being immutably divided into M+F should delve into slug sex.”

Come on guys, we could be doing more important stuff. Like hating cis men instead. Also, UCL should rejoin Stonewall. Thank you and goodnight!

edited by Coryn Gyimah